We are here because we know that schools are not working as they could, as they should, and that learning and teaching can be made much better and more meaningful in almost every situation. The concept and the function and the practice of school need to be re-designed — that’s one of our central beliefs. So — what is design? How do you go about remaking something, with thought and care and intention, but also with responsiveness and flexibility and creativity? How to we go back to scratch and engage with ideas and practices to reinvent such a broad and deep social structure, without spinning wheels aimlessly or rigidly re-inventing the same disempowering structures we’re trying to get rid of?

We need to acknowledge that the word “design” has some definitions and connotations out there which we want to embrace, and a bunch of others that we’d rather distance ourselves from. For us, design is simply a creative, intentional act of problem solving. Key to our understanding of the practice is the tension between the ideal and the practical — when we design, we are shooting for perfection even though we know that there is no perfect design, and that our very best work will always be less-than-ideal, ready to evaluate critically and then to re-make (again and again) as we learn more. This is why we insist that all designs should be iterative – we should never allow the schools we create to become encrusted in tradition; they will have to be in a perpetual state of re-design if we have any hope of meeting our democratic commitments. Also, we must say that we’re not interested in any romantic notions that the practice of design is some kind of magic unto itself, or something that can “change the world” just by being. If it’s not a tool of democracy, peace, and justice, then it’s just as likely a tool of oppression, domination, and autocracy. Enough said.

There are plenty of models, processes, and structures out there for doing design, of course. We have a few that we’ve dug into over the years, used and adapted and read about and watched from a distance. As we move into our own work, geared specifically to democratic design for democratic schools, we want to steal and borrow bits and pieces of a bunch of the best design practices we’ve found. Here’s some of our starting points:

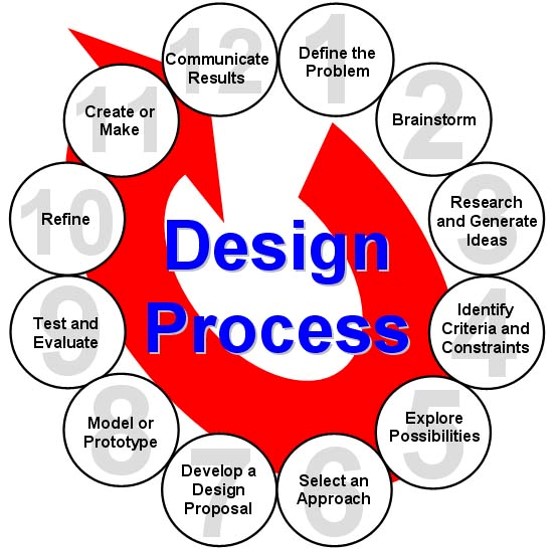

Engineering Design Process – ITEEA

Basics:

This bulky twelve-step process is the secondary-educational distillation (or extrapolation, depending on your perspective) of what professional engineers supposedly do every day. It’s cyclical, starting with a problem that needs to be solved, processing that problem in a few ways, then generating and evaluating ideas to solve it, and finally making and testing solutions. It’s crucial that the representation of the process is an endless-loop cycle: as you refine and present your design work, you discover new and persistent problems that need to be solved. These are simply opportunities to “re-iterate” the design process.

Origins:

The International Technology and Engineering Education Association is my professional organization as a Technology Education teacher. It’s worth the brief aside here to recognize the kinda turbid history of this profession — what has been variously called “shop class,” “industrial arts,” and “vocational ed.” The ITEEA was a big part of the push in the last couple decades to make this corner of the world-of-schooling more “respectable” — less about dirty and dimly-lit shops in school basements, or places to drop students who otherwise can’t seem to find success in the neat and brightly-lit academic classrooms upstairs, and more about applied academic learning. Key to this was a shift from “hard skills training” in tools and machines to “conceptual learning” about design and problem-solving. “Engineering” became a framework to underlie all “technology education” work, and this design cycle became a cornerstone.

Objectivity:

There is a major question about this process, though: do engineers actually do this? Putting aside the fact that there are an enormous variety of types of “engineering” happening in the world, and that the conditions under which “engineering” is happening are likewise crazy-diverse, can we really say that this is some kind of universal process? Knowing a few working engineers, and asking them just this question, I’ve gotten similar responses: “Yeah, this is basically what I do, but it’s not like I follow this flow chart every time I work a project…” In real-life things are always messier and more complicated. Worth noting.

Most Convincing:

What’s most convincing, though, about this model is that it is clear enough to be approachable without being too over-simplified. There’s a lot of opportunity to dig deep into questions and ideas while working it, but there’s always a next-step to keep an eye on. It’s also notable for including “Step 12 – Communicate Results.” Sharing, publishing, exhibiting, and/or distributing the work of your design is an important part of the process, to keep it from becoming to disconnected and insular.

Value to Our Work:

In our work, I think we can use this as a “baseline frame” to build the rest of our process on. It’s way too bulky to present as a simple, approachable process, but it hits the main ideas of a sequence of processes to engage in creative problem-solving, and it highlights the cyclical part of the work that is so critical — as soon as you’ve designed something, you will be presented with more problems in need of solutions.

“Design Thinking for Educators” IDEO

Basics:

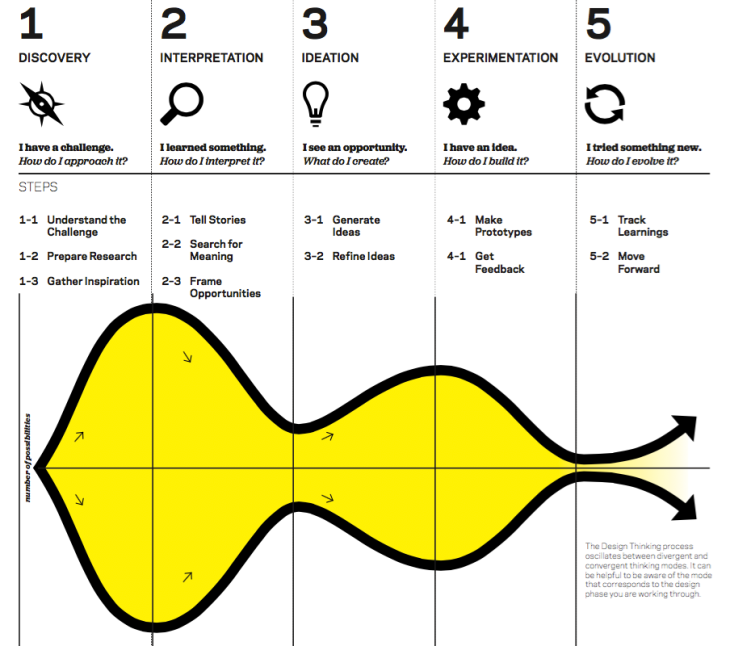

This one is fascinating because it’s written for an audience of teachers — with the explicit goal of training them to do “design thinking” in their own work (to create curriculum, spaces, or processes, or… even… whole schools…). The basic structure of the process shares a lot with the general “engineering design” framework from ITEEA — the overall arc of “Identify a problem” → “Understand the problem” → “Ideate” → “Pick and develop a solution” → “Test and repeat…” holds in this model. There are some interesting departures, though – most notably the focus on interviews as research. This seems rooted in the “tech design” idea of human-centeredness — ideal for designing institutions, maybe less-so for designing products. It is also less overtly cyclical than the previous model, though the final category “Move Forward” does indicate continued work on the design. This model is the only one to visually represent the ebbing and flowing of “convergent” and “divergent” thinking across the process, which is an important framework to understand.

Origins:

IDEO is a for-profit technology design company, who touts their achievement of “designing the first manufacturable mouse for Apple” prominently on their website. They also claim to be “pioneers of human-centered design – putting people at the center” of their design work. Without being disparaging, it is safe to say that this company is fairly emblematic of the caricature of “design” — a San Francisco firm who makes cool looking, futuristic products, and then turns their sights towards social issues in attempts to apply their industrial design concepts to bigger problems. “Tech bros” and oblivious gentrifiers suddenly aware of poverty and inequality are the accompanying caricature. Leaving these aside, it is worth noting that these ideas are not rooted in community organizing groups, social theories, or explicitly justice-oriented organizations. It could be argued that companies designing for Apple are in fact diametric opposites of these.

Objectivity:

Since this is a model proposed by a for-profit entity, though given away charitably, we have no ground to witness examples of its failure — and there must be some. They authors claim that “you can use Design Thinking to approach any challenge.” True — just as you can use autocratic personality-cult leadership to approach any challenge. The values that underlie the approach they present are extremely appealing to us and our work, so it is extremely important to temper our inclination to agree with their work with some critical thought.

Most Convincing:

The most convincing part of IDEO’s pamphlet on design thinking is the recognition that design is, in fact, a neutral description of most “problem-solving” we already do. By illuminating a structure for it, and providing simple but effective prompts to guide a designer through the process, this method seems valuable as a time-saver as much as anything. We don’t need to muck through our own attempts at recognizing, organizing, and creating a process if this one lines up with our core beliefs of community, learning, and design.

Value to Our Work:

A major value to our work is the emphasis on personal interview as a valid research method. We struggle with striking the balance between “community design” (see Emery below) and “student-design” — we wonder how we can ensure that students get the authentic experience of designing their own learning while still being responsible to the many stakeholders outside the design circle of facilitators and students. IDEO’s work gives one solution to that — if we identify our community stakeholders and prepare for meaningful interviews/listening sessions with them, then compile what we hear into stories that are significant to us, we may be able to strike this balance. If student-designers hear local non-profits explain the importance of a particular curriculum, and we continue to trust students to design the learning they need, then we have to trust them to take what they hear in these research interviews seriously and incorporate it into our design.

Nueva School’s “Design Thinking”

Basics:

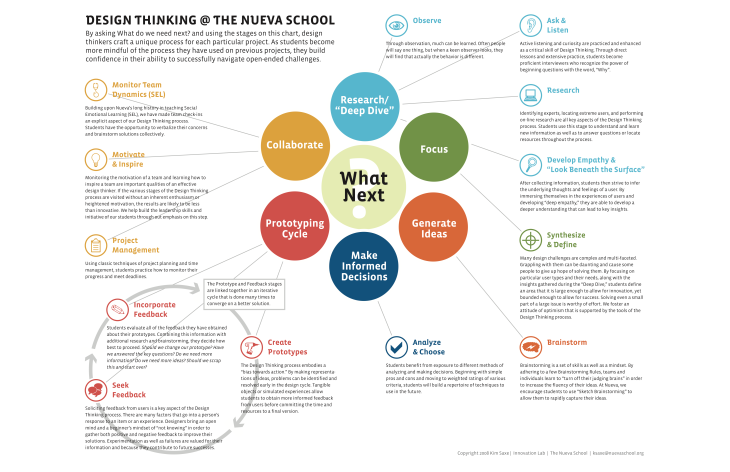

Starting to see a theme going… again the general framework of this process calls for understanding → ideating → prototyping → testing. Boilerplate by now. There are some major new contributions here, though, likely as a result of this process being geared directly for students-as-designers in a project-based learning environment. The explicit inclusion of “Collaborate” as a part of the mix — asking designers to think about and plan for how they will work together towards a common goal — is not present in either of the previous design processes we’re looking at. Also noteworthy is the inclusion of “Observe” as a key element in the research phase. More than just interviewing and asking questions, then summarizing into stories (as with IDEO) or some more generic concept of “research” that will likely lead to serial googling (as with ITEEA), Nueva School’s process calls for what might be called “close observation” of the situation, problem, and people involved in it. They also throw into the mix “identify extreme users” which is a fascinating contribution. Another big variation is splitting the “prototyping cycle” off of the larger problem-solving methodology — rather than going back to square one and re-running the entire design process, there is a dedicated, separate cycle for testing models, getting feedback, and re-prototyping.

Origins:

Nueva School is a private PreK-12 school for “high ability students” in California. If the design process in their infographic bears striking resemblance to the IDEO process previously described, that’s no accident — their “Innovation Lab” (a project-based “Design Thinking” learning space) was created “in partnership with IDEO and Stanford’s d.school.” IDEO has been examined above — but Stanford’s “d.school” is worth considering. In many ways, classes and programs here seem to be the university-level equivalent of what our own secondary-ed efforts have so far been geared towards, as their website describe it: “Experimental. Student-centered. Team-taught. Come explore our current offerings, all based on real-world projects.” Right up our alley — again, reason to be intentionally critical. They, too, draw a hard connection between conceptual “design” (an industrial idea) and social/cultura/~any kind of~ change (“Our goal is to help you use design to make change where you are.”)

Objectivity:

All silver bullets are to be looked at with serious suspicion… speaking as someone who has taught design and uses it regularly in my work and personal and political and cultural life, I find it an endlessly useful problem-solving construct. However, I’m also extremely wary of any claims that ~anything~ will work for ~everything~ and that claim about Design Thinking tends to run through IDEO and d.school and ultimately Nueva School’s curriculum. Again — there is no effort to describe limits to the application of this process. Where does “Design Thinking” fail? What are the contexts and conditions that make it inapplicable? (Does this sound unfair? These are mainly rhetorical questions for us right now — to keep us from diving headlong into a process model without thinking deeply about it. Answers are likely in the academic literature that has examined these ideas — does that literature exist? More to come…)

Most Convincing:

The most convincing idea here is that “research” should be a living, breathing, vibrant process, with deep challenges and rich moments of critical thought. Admittedly, in my past design work (which most closely followed the ITEEA model above) this was the “deadest” part of the process. Although their visual representation isn’t necessarily cyclical or even procedural, it is clear that to Nueva School, the “deep dive” research phase must happen early in any design. It even seems as if it could be the lead-off event. I also am very impressed that there is a “focus” phase that might follow this “deep dive” — I have seen many times how, after students identify and define a problem, their research fundamentally changes the nature of their project, and it can be awkward to maneuver that in the more-rigid design process. It is also extremely convincing to see “Social Emotional Learning” built into the process — I’m tempted to think this is only included because this process is written for student use, but the elements in this phase (including “Project Management” — huge!) are completely applicable to all sorts of adult/non-school collaborations I’ve been a part of, too.

Value to Our Work:

When we convene our first cohort for full-school design #1, we will be a room full of strangers. The “Collaborate” phase in this design process might give us a good framework for building that room of strangers into a team — particularly when paired and blended with other tried-and-true team-builders, like are found in Stout, for example. The greatest strength we can draw from this model, though, is the “deep dive.” I’ve always thought that we’d start with deep story-telling, talking amongst ourselves about our experiences in school and what we can learn from them, but I love the idea of going back into our old schools as pure observers — taking an almost anthropological lense to them. And interviews! Yes — asking and listening to stakeholders of all kinds to gather information about potential design ideas, problems, experiences — that will be a real gift. And the demand to consider “extreme users” — I suspect that our cohort will include kids from both extremes of the school experience (drop-outs and flunk-outs on one end, and the bored over-achiever check-out on the other — Big Picture South Burlington describes this grouping as natural to an authentic alternative), but it’s worth making that visible and considering it as part of the background of our design. Very valuable.

Merrelyn & Fred Emery’s “Search Conference/Participative Design Workshop”

Basics:

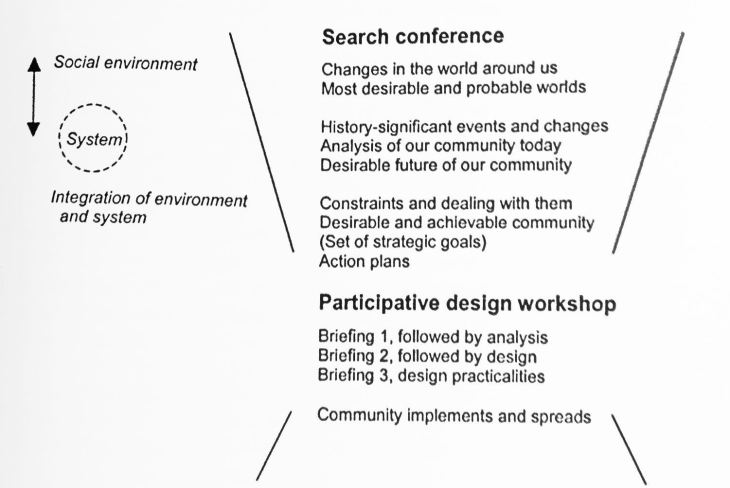

The model presented here comes from Merrelyn Emery (including work by her late partner Fred Emery), and it is described across over 40 years of scholarship and reflective practice. Because of this, and because so much of C|L|D’s work is directly built on their praxis foundations, we’ll have a lot more to say in a separate post. For this short summary, I’m highlighting the two phases of an organizational design based on the Emerys’ work: the Search Conference and the Participative Design Workshop. The Search Conference begins by gathering all the stakeholders into a multi-day, dedicated work session, facilitated by a guide trained in their model. The full group conducts an analysis of the present situation of the organization within its environment — “What are the conditions of the world around us today? Where have these come from” and “Where have we as an organization come from? Where are we now?” Then, the participants are asked to vision desirable futures both for the organization and the broader environment. To begin bridging the gap between where we find ourselves and where we want to be, constraints are identified and strategic goals and action plans are set. This signals the end of the Search Conference, and the beginning of the Participative Design Workshop. In that second section, representatives instead of full groups work to apply the action plans. There is more analysis, this time focused on the needed skills, based on a “matrix” that the Emerys created. Then comes, “Designing a Structure” — there is frustratingly little detail in their work as to a method or process to “design,” unfortunately. Compared to the other design processes, this is wide open. Finally, “Practicalities” are considered, including timetables, listing of skills and resources needed, and more action-planning. This process also varies from the previous insofar as there is no explicit “cycles” of design — the assumption seems to be that once the process is complete then the organization will be up and running in its best iteration.

Origins:

Again, the Emerys’ work is deep and profuse, and offers a lot of lessons to us as designers explicitly interested in learning, democracy, and the connections between them. For the sake of this synthesis, it is worth noting that the Search Conference and Participative Design Workshop grew originally out of social science and social psychology work toward industrial democracy in Scandinavian countries, starting in the 1960s. Fred Emery brought this work back to Australia and worked in the University system there in the 1970s to further develop a “democracy in the workplace” set of theories and practices. This work was highly esoteric in its theoretical implications, but in practice it apparently had some major successes. After Fred Emery’s passing, his partner Merrelyn continued to develop the theory and practice, and in the 1990s transitioned it away from its workplace focus and began applying Search Conferences and Participative Design Workshops at the community level, and especially in work with American school districts. It’s worth noting that somewhere in-between, other practitioners developed these ideas into what became called “Future Search,” which is similar to the Search Conference but less directly oriented at democratizing an organization, and instead using participatory methods to improve the functioning, efficiency, or innovativeness of the group (strikes me as more corporatist in this way).

Objectivity:

Fred Emery, in the earliest versions of this model in particular, made very explicit connections between his “discovery” of a concept of design (it either serves hierarchy or democracy) and a tradition of Western political and social thought. This is frustrating, particularly coming from an Australian who had easy access to a rich aboriginal tradition of democracy that ought to have bolstered and informed his theory. By placing himself in line with colonialists, he unwittingly defies his own democratic agenda, which is a shame. On the other had, as the theory and practice evolved over decades, Merrelyn Emery did not shy away from documenting and reflecting on the limits and failures of the process, which gives it a depth of credibility.

Most Convincing:

The most convincing element of the Emerys’ work, and the idea which will make their extensive praxis so central to C|L|D’s work going forward, is the reflexive relationship between a system and its environment. Without explicitly claiming it, the Emerys are repeating Bourdieu and Passeron’s thesis that cultural institutions (and particularly schools) are the site of social reproduction. Where they differ from Bourdieu is in their insistence that this cyclic and reflexive relationship – in which our organizations are modeled on the hierarchies and structures of the broader society, and in turn ensure that we are all effectively enculturated to that hierarchy – can be disrupted by re-designing institutions at the “ground level.” The Emerys claim that a “design principle” of equality and democracy can be built into any organization, then multiple organizations, and so on until it becomes the central organizing principle of all social and political forms — hence their title Participative Design for Participative Democracy. Redesigning workplaces (and, later, schools and communities) to be participatory in nature can and should lead to a form of democratic politics and society which is broadly participatory.

Value to Our Work:

What we will take from this is a firm commitment to the “long game” of our design work. We are approaching school design the way we are from a political commitment to dignity, equality, and justice — this is far more important than the discrete ideas we may have developed as “design experts” over our years working to make schools better. If our schools are to be sites of learning for democracy, for participatory community control over the institutions of each and all of our lives, then our schools must be designed in, by, and through participatory democracy. Start where we are, in other words, but never get lost in the immediacy of that work.

*Note: The Emerys’ work has led us into an exploration of the stand-alone field of “Participatory Design” — a practice and theory that seems to have grown from the Information Technology profession, and which expresses a similar fundamental concept: the end users of a system or product ought to have a major voice and role in designing that system or product. We’re just starting down the road toward understanding this field and its implications for our work — stay tuned!

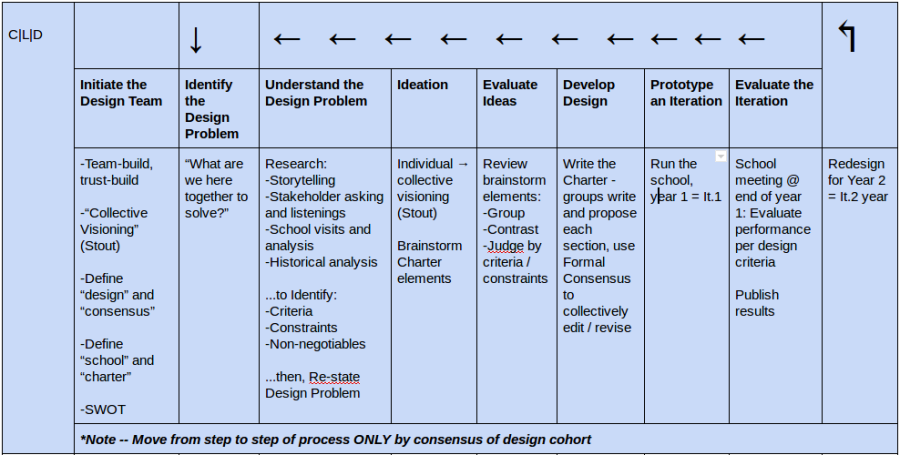

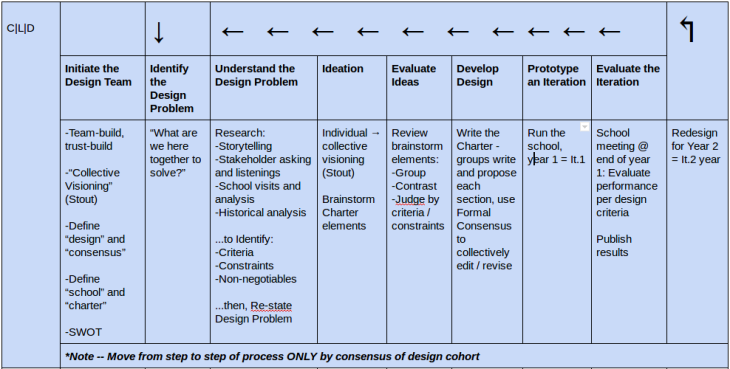

Synthesis

This is our best first-thought version of a design process — a key element in the curriculum we are proposing. How do you create a new school in participatory design with the learners who will populate that school? Once we get a design cohort in one room together, what do we actually do together? Here’s how we think it might go (subject, of course, to endless revisions — and to some better visualization along the way, eventually):

What are we missing? What can we re-think? What won’t work? Why?